Notes from a transition

I’m transitioning in my organization. I used to be part of the the IBC team, where I held a mixed role (product/project lead). From there, I'm switching to a more focused role (product lead) in the Comet team.

This change started since ~November last year, but it’s been happening at a slow pace. Given that we’re still a young and relatively small organization, I expect I will continue interacting and contributing to the IBC team for a long period to come.

The change has been very motivating and exciting.

As part of the change, I read a book called “The first 90 days” by Michael Watkins. It proved a very useful exercise. I learned several important principles applicable to transitions, and also more broadly, concerning leadership and organizations.

Below are my reflections from reading this book. I grouped them in three parts: (1) concepts, (2) principles, (3) and observations. The book doesn’t have these 3 categories, so this is purely my way of understanding what I learned. All credits go to Watkins for synthesizing these ideas so well in his book.

1. Key concepts

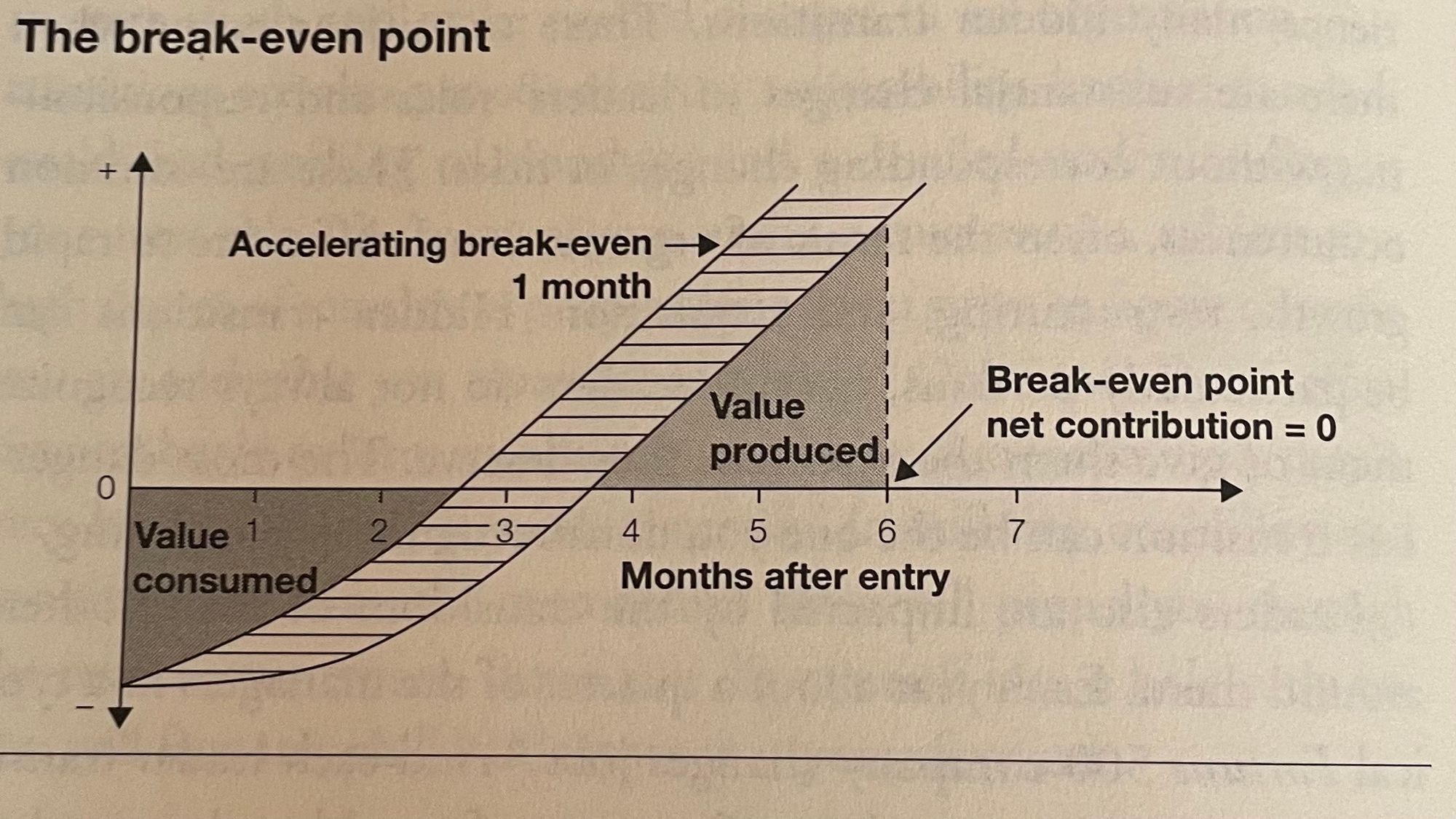

Break-even point. The break-even point defines the moment when a person starts bringing a net-positive contribution in their new role.

It’s simple: When I join a new team, I will typically be onboarding and requiring a lot of support. I am not contributing positively, but taking away resources from the team instead. When the cumulative impact of my onboarding and my contributions becomes positive, which takes several months typically, I will have reached the break-even point.

Our onboarding plans at Informal typically comprise explicit expectations of early wins. These are important psychologically for the person who is onboarding, but also to accelerate towards reaching the break-even point.

We also tag a theme to each of the first 3 months of onboarding. First is learning. Second month is contributing. Third is along the lines of owning. These themes suggest that only after the second or third month is a person able to go from a consuming state to a producing state. Interestingly, this is similar to what the picture above describes.

Action imperative. This is the tendency to want to take action. For example, to kick-off certain initiatives, to recommend a decision, to introduce new plans or processes.

Taking action is very tempting and proved a trap for me also. In my previous team I felt like I had a very good understanding of how things worked. So it was difficult (as part of a new team) to abstain and play it humble. Within my first few weeks I already started taking concrete steps to hire an intern on a project that I thought would be appropriate. This didn’t pan out for multiple reasons. Most relevant for this discussion is because I didn’t understand the team dynamics and hiring needs, nor the allocation of projects and the style in which decisions are made in this team. Initially, it felt like a big failure, but I realized afterwards that this was a clear case of the action imperative pitfall at play.

Types of changes. There’s five typical situations that someone will encounter when taking on a new role.

- Start-up,

- Turnaround,

- Accelerated growth,

- Realignment, and

- Sustaining success.

The acronym formed is STARS.

Let's take them one by one. In a startup there is usually a lot of initiative and enthusiasm, while many supporting elements for growth are missing and need to be established. For someone who is joining a troubled group, they will typically encounter the turnaround situation. Similar to Warhol's quote at the top of this post, in such a situation some things need to change. A person joining the team of a successful product might be in an accelerated growth or sustaining success situation. A realignment is a subtle situation that an organization might face where it is missing the vitality it previously had, and it is not obvious that it might be in need of a change. For a complete description, Watkins has this article explaining STARS.

In practice, there’s no such thing as a clear, single situation surrounding a role change. Rather, it will be a mix of different types of situations across different dimensions, e.g., the team might be in a turnaround phase, while the product they are building is sustaining success, while the broader organization is experiencing accelerated growth.

I found the STARS framework particularly handy for diagnosing the organization and the team. Understanding the nuances among the different situations leads to better situate oneself and orient towards providing what is needed for the particular situation. This would be in contrast to falling prey to the action imperative or to habits I have formed over the years.

2. Principles

Egos. The density of strong egos increases with the levels of managements. Put differently, the higher a level, the more likely it is to encounter people with stronger egos, more influence, or more fluency in politics or persuasion. Such skills become more relevant, and part of the reason is because higher levels of management confront problems that are less objective, more ambiguous and complex.

This is normal. The difficulty is that it can trip up engineer-style thinkers, who prefer to think in objective terms, while politics are held in contempt, typically. This is also the case for me. Understanding the reality of egos was one of the most surprising observations from this book. It helped explain a lot of things about navigating conflicts and understanding relationships in an organization, so I treat it as a principle.

New roles have unknown unknowns. There are elements of culture, history, and context that each new role comprises, and we are neither aware nor do we understand them.

Explicit preparation goes a long way towards preparing for a new role. This is because preparation can turn unknown unknowns into known unknowns or unknown knowns, by simply listening to others, for example, or reading about the past of the team. A interesting approach to doing this is the career cold start algorithm of Andrew Bosworth.

One corollary I can draw from this principle: What used to be a strength in my previous role might well be a weakness in the new role. For a concrete example, in each role I develop comfort zones. These are activities that I become skilled at doing because I practice them often, so I get a rich experience and nuanced understanding of them. They become almost automatic. The example I gave above about trying to hire an intern and failing is again relevant, because that represented comfort zone for me.

Everyone has comfort zones, it might be networking, debugging certain kinds of problems, or designing within certain constraints. Comfort zones are relevant because they are what we know, so they are a major potential distraction from things we don’t yet know.

This principle suggests a concrete solution to the problem of action imperative I mentioned above. Specifically, it would be better to focus on learning and adapting myself, and if I tend to veer into wanting to take action, or if I fall into a comfort zone, that’s a red flag to myself that I might be in a comfort zone, refusing or avoiding to function constructively in my new role. I found that setting a few explicit reminders and blocks of time in my calendar to remember about this was already very helpful.

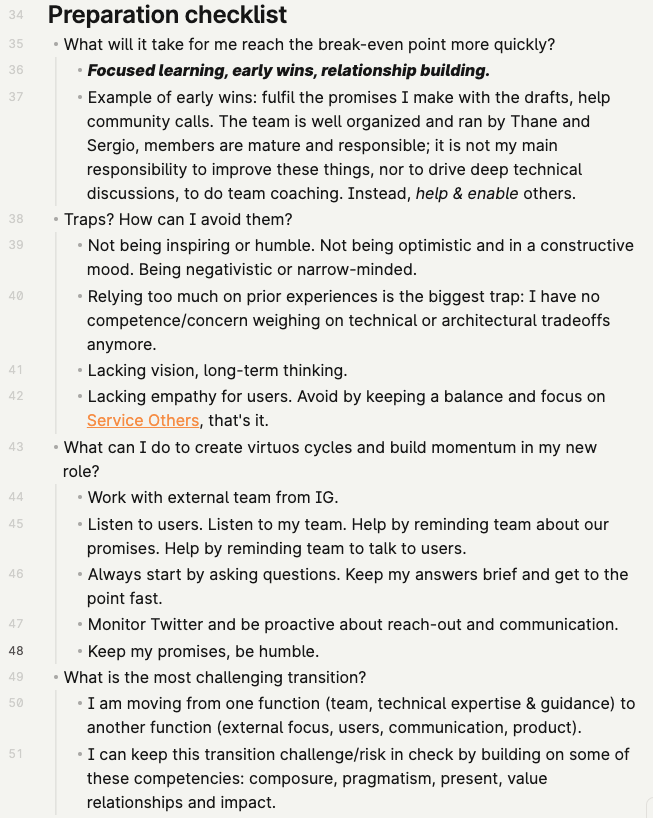

After the experience with failing to hire the intern, I took preparation and deliberate learning more seriously. Below is a snippet of some reflection to help steer myself in the new role and avoid traps.

Push vs. pull. This one is about alignment. What motivates people to work together on common goals, instead of pursuing their own agenda? One way to answer that is that there’s factors that push people, plus factors that pull them together towards a goal. I like this way of decomposing alignment because it’s very simple.

Examples of factors that push someone are roadmaps and plans, social expectations, negotiations, or incentives of most kinds. Factors that pull people seem to work primarily by inspiring them to action. These are vision statements usually, but I think there’s also deeper elements, such as shared values and common aspirations about the future.

This push/pull discussion is relevant during onboarding. In a new role there is usually little or no pre-existing trust. This push/pull framework proposes ways to build alignment and trust incrementally across multiple thrusts.

On framing discussions: Logos, ethos, pathos. There are three types of arguments that are at our disposal when we are writing a document. Knowing this can help frame the discussion better, and marshal the arguments more firmly. This is especially relevant if the writing is not scientific nor purely technical.

The logos category of arguments speak to our logical facilities. These invoke facts, observations drawn through the scientific method, and generally consist of logical arguments. Ethos arguments rest on invocations of principles and values. They draw their strength by connecting the audience to certain beliefs they are holding. Pathos is about emotions, and storytelling is relevant here.

Being an effective communicator means both knowing these different kinds of arguments and also knowing when it is appropriate to use each. This breakdown into logos, ethos, and pathos is inspired from Aristotle (“Art of Rhetoric”).

Planning versus collective learning. This is about executing a change, such as introducing a new process, changing the habits of a team or its structure. A leader can execute such a change generally by (a) planning it, or (b) by employing a collective learning approach. The difference between the two is that changing something through a planned approach works only if certain conditions are met. Watkins calls these conditions "supporting planks" (pg. 132).

The most important condition in my opinion is the diagnostic. If I have the expertise necessary to articulate the root causes of the problem I’m trying to solve and why is that a problem in the first place, then I can likely diagnose the need for change. Without this "supporting plank," it's unlikely I can succeed in that change by planning it. Instead, I would be more successful using a collective learning approach.

Other conditions to run a planned change successfully:

- Support and awareness: Are sufficient people aware that something is not right and should change? Do I have the support of those I need for the change to go through?

- Plan: Do I have the ability to formulate a step-by-step approach to do the change?

I have seen a few initiatives for changes that did not go through. What was missing, briefly, was an accurate diagnostic. Like a domino effect, the inaccurate diagnostic made the team confused about the proposed change. It also made the solution inconsistent with the problem, and amassing support was therefore impossible.

Going back to the STARS situations described earlier, I think the collective learning approach is appropriate in particular in realignment situations.

A relevant discussion on this topic is a recent post by John Cutler.

3. Interesting observations

Golden rule of transitions. This rule says to treat those encountering in my new role with the same deliberate care as I am treating myself. It's probably obvious why this is important, but it's worth emphasizing:

They are also experiencing a transition because they need to learn to work with me.

This seems very compassionate. Initially, I found that it was very difficult to apply this in practice. There was a large amount of learning I wanted to do, and many new habits I needed to form, while renouncing old ones. This left limited capacity for concerns "about others." One encouraging insight I had was to understand that helping them helps me, akin to enlightened self-interest. This insight helped a lot.

Something else that helped was sequencing. It's fine if I spent my first month focusing more on personal priorities and orientation. Then in the second (third, fourth, and so on..) month I felt less pressure for personal priorities, which unlocked time in my schedule to approach my onboarding as a group effort, rather than a solo mercenary.

TOWS instead of SWOT. I only used the SWOT framework a couple of times. Each time it felt forced. Using SWOT was insightful, but I was not impressed with the results.

I never considered there might a correct way to use this tool, but it turns out there is. Start with the environment, namely the TO elements (Threats, Opportunities), then proceed with the internal elements (Strengths, Weaknesses). I haven’t tried this yet, but will do the next time I'll need to.

The hero/steward spectrum of leadership. In my understanding, a hero is the type of leader that is in the trenches, prepared for "war" at all times, has firm positions, and may be prone to micromanaging those around him. A steward, in contrast, is the type of leader that approaches interactions with a lighter touch, is OK with compromises and long-term, slow initiatives.

The hero and steward are archetypes. They represent end points on a spectrum of leadership styles. Ideally, I would be able to shift my style across this spectrum depending on the situations I find myself in. That is difficult, but it’s a good start to be aware of these frontiers and their distinctions. Personally I am inclined towards the steward approach of doing things.

For a fuller description, I’ll refer again to the same article by Watkins and would encourage reading that.

Take responsibility for making it work with my customer. My customer is the person I make promises to, or the one I report to. This idea is about managing up, making that relation work for me, in the fullest sense of that phrase.

I found this an interesting observation because I tend to err on the side of autonomy. I avoid being too proactive in managing others, whether it is "up" or "down". (Partly, this has to do with my bias towards the steward style of leadership.) This can be damaging during periods of transition, and the book makes a compelling case for the ways in which my customer can be a critical support.

Under normal conditions, it is both fun and fulfilling for me to have a lot of room for maneuvers, which often can translate into making me seem aloof. During my recent transition, I practiced the habit of thinking deliberately about the support I need from my managers and asking explicitly for that. I anticipated it might be awkward, but was pleasantly surprised at how much initiative and help that ask generated in response.

Briefly, the major learning for me here was to not hesitate to reach out for support during transitions. Being autonomous is good, but being autonomous after transitions is better.

Underpromise and overdeliver The tactic proposed is to employ underpromising of results and to strive to overdeliver on what is expected of me. This tactic feels both manipulative and wise at the same time. I think it depends a lot on the situation and the level of trust, as well as the culture.

I will end with this one. I’m still thinking about it, so I'm approaching it with caution, but it does seem there are uses for this tactic out there.

Conclusion

Transitions are fun and exciting times. As a general conclusion, I found that these kind of periods tend to push our humility and patience to the limit. I think this is a recurring theme among the observations here.

A few of these lessons appeared to me Machiavellian at first sight. I realize that’s naive. Since human organizations are incredibly complex, it's not as simple as "this is Machiavellian". Organizations tend to be even more complex at stages of transition. So there's no surprise there’s such a wealth of lessons and nuanced concepts we can use to navigate and function better in our roles, especially during transitions.

Comments ()